+86 18101795790

+86 18101795790

Contact:Gensors

Phone:+86 18101795790

TEL:+86 021-67733633

Email:sales@bmbond.com

Address:22, Lane 123 Shenmei Road Pudong New District Shanghai, China

In the realm of aerodynamics—the wind tunnel—how do we accurately "see" the pressure imprint left by air on

an object's surface? This challenge is particularly critical in low-speed wind tunnels, where seemingly gentle flows

conceal complex underlying mechanics. Today, we explore a transformative technology: the Pressure Scanner.

With its exceptional performance, it has fundamentally reshaped low-speed wind tunnel testing, becoming an

indispensable efficiency engine in modern aerodynamic research.

I. Traditional Bottlenecks: From Sequential Scanning to Instant Snapshots

Before pressure scanners, wind tunnel experiments relied on traditional manometers (like U-tube manometers) or

mechanical scanivalves with a single high-precision sensor. While reliable, these systems had significant limitations:

Low Measurement Efficiency: Mechanical scanivalves sequentially connected each pressure port to a single sensor

via a rotating valve. This meant data from hundreds of points were collected one after another, often taking minutes

or even longer for a full surface pressure map.

Lack of Data Synchronization: Because measurements were sequential, it was impossible to obtain a full-field

pressure distribution across the model surface at the same instant. This "time lag" caused data distortion in unsteady

flow or dynamically changing model attitude tests, failing to capture the true physical picture.

High System Complexity: Numerous pressure tubes routed from inside the model not only complicated the model's

design but also caused signal attenuation and phase lag due to the long tubing, adversely affecting dynamic

response.

These bottlenecks severely constrained experimental efficiency and data fidelity, especially in low-speed wind

tunnels requiring high-density, high-dynamic pressure measurements for studies like aircraft wing flow, automotive

aerodynamics, and building wind loads.

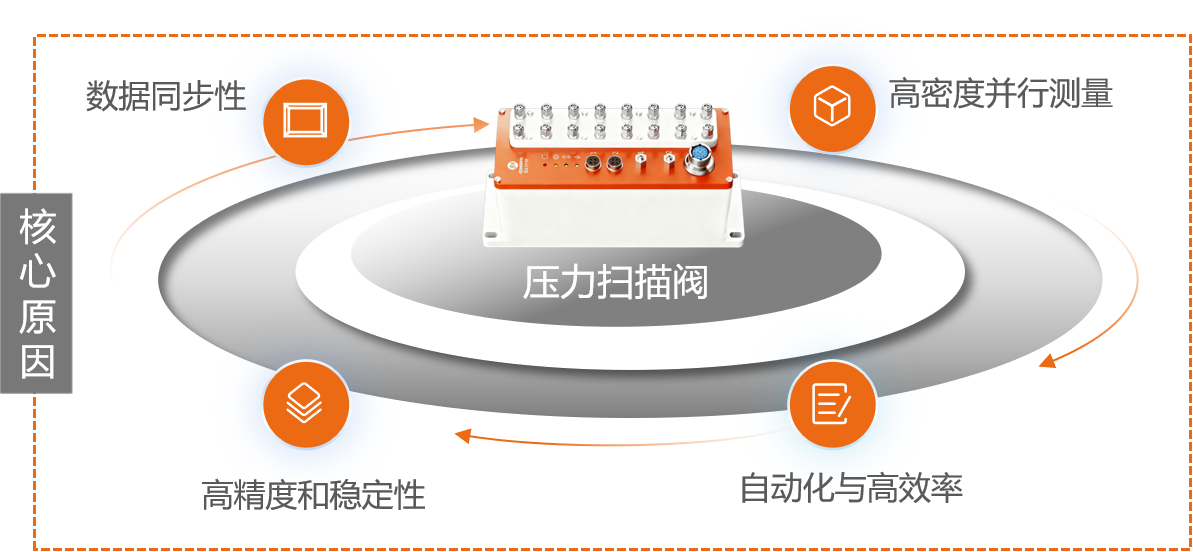

II. Technological Innovation: Core Principles and Advantages of the Pressure Scanner

The core of pressure scanner technology lies in replacing "serial" with "parallel" operation. Its basic structure

integrates an array (typically 16, 32, 48, or 64) of high-precision silicon piezoresistive sensors and a multiplexing

electronic switch within a robust valve body. Each sensor is independently and permanently connected to a

pressure channel.

Its workflow can be summarized as:

Synchronous Pressurization: Static or total pressures from all surface taps are transmitted simultaneously via

internal tubing to their corresponding sensors within the scanner.

Parallel Sensing: Each sensor converts the physical pressure signal into an electrical signal in real-time.

High-Speed Polling: An internal high-speed electronic switch reads the electrical signals from each sensor

sequentially at very high frequencies (up to tens of thousands of scans per second).

Centralized Output: Data is transmitted via a bus (e.g., Ethernet, USB) to a host computer, ultimately yielding a

highly time-synchronized "snapshot" of the full-field pressure.

This principle delivers revolutionary advantages:

High Data Synchronization & Efficiency: A single scan captures pressure data from all points on the model surface

at the same microsecond-level moment, drastically improving test efficiency and enabling the study of unsteady

phenomena like vortex shedding and flutter onset.

Superior Measurement Accuracy & Consistency: All channels share the same reference pressure and temperature

compensation environment, effectively eliminating systematic errors from individual sensor variations in traditional

multi-sensor systems and ensuring data consistency.

High Channel Density & Scalability: Modular design allows multiple scanner units to be daisy-chained, easily

building large systems with hundreds or even thousands of channels to meet high-resolution measurement demands.

Simplified Model & Tubing Design: The scanner's compact size allows installation directly inside the wind tunnel

test section or the model cavity, minimizing pressure tubing length. This reduces signal lag and tubing capacitance,

enhancing dynamic response capability.

III. Typical Applications in Low-Speed Wind Tunnels

In low-speed wind tunnels (typically Mach number Ma < 0.3), the value of pressure scanners is fully realized:

Aircraft Model Surface Pressure Measurement: With hundreds of pressure taps on wings and tails, scanner systems

allow researchers to precisely map pressure coefficient (Cp) distribution clouds at various angles of attack and

sideslip. This provides direct, reliable data for validating CFD simulations, optimizing airfoil design, and studying

stall characteristics.

Automotive Aerodynamics Research: Measuring pressure distribution on car bodies helps analyze lift and drag

causes and locate vortex generation areas, guiding shape optimization, wind noise reduction, and fuel efficiency

improvements. High synchronization is crucial for studying transient flow structures like A-pillar vortices.

Building & Structural Wind Engineering: Dense arrays of taps on scaled models of buildings and bridges enable

synchronous measurement of wind pressure distribution under simulated atmospheric boundary layer winds.

This data is essential for evaluating structural wind loads, studying wind-induced vibrations, and ensuring building

safety.

Unsteady Flow & Dynamic Testing: In dynamic tests involving forced or free oscillation, the scanner's high-speed

acquisition captures the complete pressure history relative to phase, opening the door to in-depth study of

aeroelastic phenomena like flutter and buffeting.

Conclusion

In a sense, the pressure scanner is more than just an instrument; it is a transformer of "data perspective." It

elevates our understanding of flow from a blurred, lagging "flipbook" to a clear, real-time "high-definition movie.

" In the pursuit of higher efficiency, more precise data, and deeper insights into flow mechanics within low-speed

wind tunnels, the pressure scanner has become an indispensable core power driving scientific and engineering

progress. It continuously helps engineers and scientists capture the intricate imprints left by the invisible wind,

forging safer, more efficient, and more innovative aircraft, vehicles, and structures.

Copyright © 2009-2025 BM Genuine Sensing Technology (Shanghai)Co.,Ltd. All Rights Reserved.